The Moon Will Teach You

By Pedro Gómez-Egaña

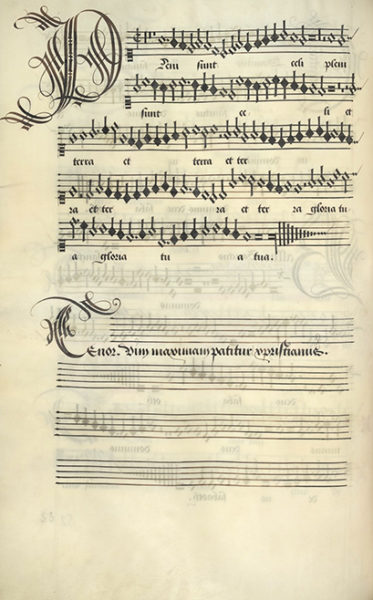

B-MEa-ms-ss or the so-called Mechelen Choir book (“Mechels Koorboek”), ca. 1496–1534, Stadsarchief Mechelen, © Alamire Digital Lab

Some of the most prominent music produced in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was linked to the spread of polyphonic choral compositions. This music was usually interpreted from handwritten parts in the form of choir books with music and lyrics laid out for individual voices (typically soprano and tenor on the left-hand pages, and alto and bass on the right-hand pages). While at this time the printing press had already announced a move toward standardized and a universally understood set of signs for musical notation, these choir books saw a wealth of experimental and innovative approaches in their writing, particularly in the Low Countries.

One such practice was that of inserting enigmatic text inscriptions, similar to riddles, as a way of instructing the full intention of a composer. Drawing from biblical, as well as classical sources, the deciphering of these short texts could reveal the composer’s ideas in a playful and cryptic way. Some of these texts indicate the addition of contrapuntal lines, the possibility of voices beginning at different times, or even the possibility of reading a part backward. An example is the inscription “Iustitia et pax se osculatae sunt” [Justice and Peace have kissed each other], in Ottaviano Petrucci’s Motetti A, which signals a retrograde interpretation of the score, or “Dij faciant sine me non moriatur ego” [May the Gods bring it about that “I” does not die with me], which indicates an omission of pauses.

The practice of inserting enigmatic inscriptions in music appears to be counterproductive as they purposefully interrupt the interpretation of a score, but they played other interesting roles. Apart from being a satisfying diversion for scribes, musicians, and patrons, these riddles also manifested social boundaries between those with and those without the cultural and intellectual training to engage with them. These small fragments were also used as a way to relate to, and comment on, other compositions, as well as citing current events. Finally, the inscriptions also presented themselves as a kind of signature or proof of a certain authenticity as part of a scribal workshop, or as belonging to a particular patron.

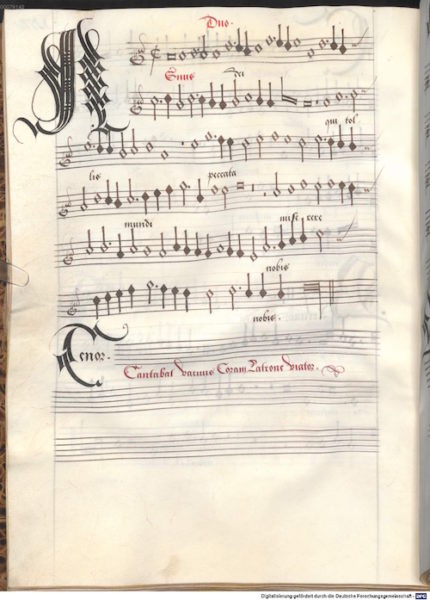

Among the most evocative practices of enigmatic inscriptions in choral parts is that of the “tacet canons” of the workshop of Petrus Alamire. These text fragments had the aim of instructing the singer to remain silent during a specific passage in the composition and to harness the moment of silence as a break in the linearity that dominates any score. Rather than leaving the page empty, tacet inscriptions encourage a certain introspection, a sense of religious meditation, or existential disposition, and establish a creative and critical distance to the music and text while the other singers are busy interpreting in the moment.

Example of a tacet inscription on Mathieu Gascone’s Missa Myn Heert, Agnus II, T. Cantabat vacuus coam latrone viator (The traveller without goods sang in the highwayman’s face), Munich F Manuscript – Petrus Alamire, courtesy of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München

However, as the printing press developed and took prominence over handwritten scores, standardized modes of notation, as well as a wider distribution of musical parts and scores, led to the disappearance of the riddle culture in music writing. The obscure and multi-layered approach of manuscripts gave way to a semantic immediacy that matched the automation and standardization that industrial printing encouraged. Some of the enigmatic text inscriptions have evolved to become compact qualifiers of volume, intensity, or speed, such as in the Italian “con fuoco” [with fire] or “Festoso” [festive]. Silence, however, has had the most poignant reduction in musical writing, becoming simply the word “tacet” or in many cases, no word at all.

References:

Blackburn, Bonnie J. “The eloquence of silence: tacet inscriptions in the Alamire manuscripts.”

In Citation and Authority in Medieval and Renaissance Musical Culture: Learning from the Learned, edited by S. Clark and E. E. Leach, 206–24. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2005.

Schiltz, Katelijne. Music and Riddle Culture in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Kellman, H., ed. The Treasury of Petrus Alamire. Music and Art in Flemish Court Manuscripts, 1500–1535. Ludion Gent Amsterdam: The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Special thanks to Stratton Bull and the Alamire Foundation, Leuven.